CAR FERRYRAMON

AND THE SUISUN BAY CROSSING

The Suisun Bay ferry crossing was one of Sacramento Northern's most unique features. Although there was at least one other interurban line with a ferry, SN's was arguably the most sophisticated operation of its type in the United States. With 41 years of service, it was also probably the longest-lived.

The Oakland, Antioch & Eastern survey required a crossing of Suisun Bay near the meeting point of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. The crossing point chosen was between West Pittsburg and Chipps Island, only 2,600 feet. Unfortunately, a high-level draw bridge with long approaches would be required to clear the heavy ship traffic. The two-mile long bridge's estimated price tag was $1.5 million. Since there wasn't that much money in the till, the management chose to build a ferry as a "temporary" solution until business improved. Business never did improve that much, and the ferries shuttled across the channel for many years.

The first ferry was Bridgit, a wooden-hulled, double-ended boat powered by a gasoline engine. The ferry was built by Schultze, Robertson & Schultze of San Francisco. At 186 feet in length, she could carry a train of six passenger cars. The name Bridgit was actually a pun on the words "bridge it", and was not a woman's name at all. Launched in 1913, Bridgit lasted but one year before being destroyed by fire on May 17, 1914.

After the loss of the first ferry, the OA&E tried a barge called Harry lashed between two tugs. The barge made only one crossing before being deemed too unstable. For a while the railroad used rented tugs and car floats from the Santa Fe and Western Pacific until a new ferry could be delivered.

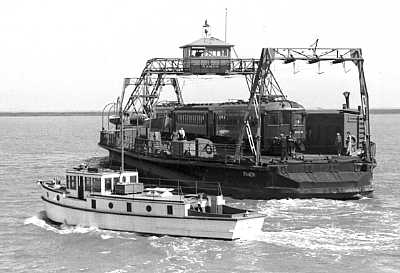

For a permanent solution, the OA&E turned to the nearby Lanteri Shipyard of Pittsburg. Their design was for a 270-foot double-ended craft, essentially a powered barge. To save construction time, the ferry was built entirely with flat steel sheet and did not have any curved plates in its hull. The boat was divided into 11 watertight compartments, making the vessel practically unsinkable. A 600-horsepower distillate engine provided propulsion. Up to six passenger cars, or 10 freight cars, could be handled on the deck. Christened Ramon, the new ferry entered service on January 3, 1915.

Ramon was very difficult to maneuver, partly due to the boxy shape of its hull. Having no keel, it was easily pushed about by the strong winds and treacherous currents of the delta. This made working the ship into the slips extremely tricky at times and certainly played havoc with the passenger schedules. The engine was barely powerful enough to move the ferry in calm waters, and Ramon often had to be taken in tow by tugs when the weather was bad. More than once the ferry broke her anchors and floated at the mercy of the tide until a tug could be summoned.

Ramon was taken out of service once a year for maintenance and inspection. The inspections were usually done at a Union Iron Works shipyard in Alameda or San Francisco, with repair crews working around the clock to minimize disruptions of the train schedules. Downtime was usually about three days. During those periods, the company launches Laguna or Countess were substituted. Special trains met the launches on each side of the channel and then returned to their terminals. Since most of the SN's parlor cars were single-ended and there was no turning facility at Chipps, the special trains lacked the fancy cars. Freight cars were routed between Sacramento and Stockton over the Western Pacific, and then via the Santa Fe to Pittsburg.

One of Ramon's most interesting features was a small galley and dining room for passengers. Considering that timetables allowed only eight or nine minutes for the crossing, the dining room was not really practical. Of course, when the ship was having trouble docking, there was plenty of time for passengers to finish their meals, unless they were seasick. For some, lunch on Ramon must have given a whole new meaning to "rail" travel. Both coach and first-class passengers both could eat a more leisurely, but also more expensive, meal in the parlor car on featured trains. They were spared indigestion from wolfing down their food, though most passengers sometimes must have democratically suffered from "mal de mer" during rough crossings. The lunch counter was later moved to a 13 X 70-foot structure at deck level in 1926, which might have speeded up meals a bit.

For several years, Ramon's lunch counter was operated by George Dunlap, a prominent black businessman and caterer from Sacramento. His crew consisted of a cook, a steward and a waiter, all black men. Dunlap also had a contract to operate the SN's dining car services. Ramon's dining facilities were closed in 1940 with the end of passenger service.

At least into Ramon's SF-S years, there was also a small stand at deck level that sold newspapers, tobacco, candy and sundries. It may have continued in operation even after the lunch counter was moved above deck. Little is known about this operation, and no record has yet surfaced about when it was discontinued.

The SN made continual improvements to the ferry to meet strict U.S. Coast Guard regulations. Ramon received a locomotive type headlight in 1930, a marine telephone linking the pilot house and the engine room in 1934, updated fire protection in 1937 and again in 1953, new ventilation equipment in 1944, and a rather late removal of the dining room in 1948.

Passenger service via the ferry ended in 1940, though freight service continued throughout World War II and beyond. However, the ferry was a traffic bottleneck and expensive to operate. In addition, the WP was concerned about the ferry's ability to handle the valuable steel traffic to Pittsburg. Ramon was taken out of service for regular maintenance on April 7, 1954, and the inspection indicated major structural repairs were needed. When the WP management received an estimate of over $300,000 to fix the boat, they jumped at the chance to immediately end the ferry crossing. Ramon was sold for scrap August 8, 1954 to the Learner Co. for $5,000. The boat was broken up at nearby Antioch, not far from where she had been built some 40 years earlier. One of her massive pistons is reported to have been donated to the Smithsonian Institution and probably still resides in one of their dim warehouses awaiting the inspection of curious historians. So ended one of the SN's most unusual operations.

Fire was constant danger to the slips and the approach trestles. Both were protected by a system of sprinklers, fed from large water tanks. There were also fire watchmen stationed on both piers 24-hours a day. The slip at Chipps was eventually destroyed by fire in 1956, but that was several years after ferry service had ended. At the time of the fire, contractors were already dismantling the slip.

Mention was made earlier of launches which backed up Ramon. The first of the these was Laguna, which was bought by the OA&E to shuttle passengers across the strait after Bridgit was lost to fire. The second boat was Countess, purchased used in 1920 by the SF-S. She had a 60-foot long wooden hull and was powered by an Atlas six-cylinder engine driving a screw propeller. Countess had been built at Sacramento in 1912. She was retired November 25, 1942, and sold for $970.87. A similar boat named Legonia was purchased in March 1942. This last launch also had a wooden hull, and was driven by an 80 horsepower engine. Legonia was sold off in January 1946. When not needed for shuttle service, the launches were used as general work boats. They were also available for charter and saw frequent use by duck hunting clubs.